Why you’re not getting more done — and what to do about it

For this month's featured article we're exploring why sometimes it's difficult to focus on important projects, and more importantly, a creative way to leverage the power of your brain to increase your productivity, focus for longer periods of time, and get into flow state.

I think you'll enjoy it.

Cheers to Evolution of Humanity,

Sunny Nason

The road to productivity is paved with good intentions. But, oh — the emails, the incessant dings and pings and rings, the flashing notices on screen, your grumbling tummy, that dog barking somewhere on the block, the dirty dishes, that nagging drip in the bathroom sink that reallyreallyshouldgetfixedrightnow.

It’s enough to make a person crazy, isn’t it? Why is it so hard to just focus and concentrate on what we need to get done?

Like most things, the answer lies quietly in the human brain. And unless we understand why something is happening at that deep level, it’s almost impossible to transform what isn’t serving us into something that can serve us.

We’ve written before about the power of habit in our brains, and why it can be so challenging to shift behaviors. And we’ve also talked about how specific brain waves affect our emotions, physiological states, and levels of attention.

The same part of our brains that resists change and newness is also insanely attracted to novelty.

That might sound like a contradiction. So what’s the difference?

Imagine our ancestors out on the savannah thousands of years ago. They likely had figured out a routine that worked for them to gather and hunt food, to sleep at night, to protect their families. So in that way, newness was resisted: if we did this, and it worked, and we’re still alive, there’s no reason to change anything.

But think of this: A rustling in the grass. A flash of eyes in the glow of firelight. The slight movement in the distance, and a shape that’s barely distinguishable from the surroundings. The discovery of a new fruit that could sustain or be poisonous. The smell on the wind of coming rain, which could mean much-needed fresh water or a devastating storm. That’s novelty.

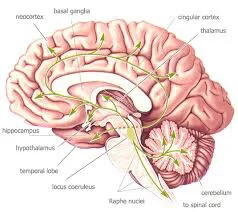

Our brains are built to be highly attuned to any blip on our sensory radar, because that’s what ensured our survival. An area called the locus coeruleus especially is responsible for kicking out neurotransmitters to the limbic system that tell the brain how to respond to stimuli and whether or not it’s supposed to be calm or on high alert. The locus coeruleus enervates with the hypothalamus and the amygdala — which process emotion and memory — and this is why even memories of events can trigger a physical stress response in our bodies. Not surprisingly, studies have also linked the locus coeruleus with our waking and sleeping cycles.

So, a sensory-distraction moment (which all takes place in milliseconds) could look like this: you hear a loud bang, which startles you. The auditory input goes to your locus coeruleus and initiates a stress response. If you are able to identify that the noise came from a backfiring old car, your brain will process the memory that this is non-threatening and will release calming neurotransmitters to halt the high alert. On the other hand, if you look and see a person nearby wielding a gun, your brain will kick everything up even more, sending more blood flow to your extremities and preparing your body for flight.

Today, the locus coeruleus can still help us the way it did for our ancestors — if you’ve read Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink, you know the incredible power of our brains to sense and process in a snap the minute clues in our environment that can lead to life-saving choices.

But it also ensures our susceptibility to distraction, especially with the constant surround of stimuli of all kinds, as the brain is continually starting and stopping responses to perceived tiny “emergencies.”

Fortunately, we do have a couple of mechanisms in our brains that allow us to adapt to the frenzy, and some people actually find it easier to work in a louder environment as opposed to a very quiet one.

One mechanism is called habituation. This occurs when our brains reach what neuroscientists refer to as cognitive load. Essentially, our senses just get overloaded, and this allows our brain to amalgamate and filter out background noise for a short period of time (usually about 20 minutes), to register it as “white noise” so that we can concentrate on one task like reading or carrying on a conversation. But it’s not really a long-term solution if you’re looking to really focus on a longer project, and it doesn’t help us get into a flow state.

Another ally we have in the quest for paying attention is our frontal cortices. This is the seat of our executive function; it acts like a project manager for our environment and constantly sends signals to the rest of our brain, especially the limbic system, to calm down.

So what can help our higher brains be better project managers, improve our ability to focus for longer periods of time, and get into flow state?

Anything that sends energy to the prefrontal cortex will help build the “muscle” of attention in your brain — and we’ve talked about those things here in these newsletters: getting outdoors, walking a lot and walking barefoot, a consistent meditative practice, intentional gratitude, getting regular exercise, whole-food nutrition, and activating the frontal cortices through your Higher Brain Living® sessions.

One unique finding in the science of focus has to do with music — specifically, instrumental music that plays at about 60 beats per minute. According to the research, music at this rate elevates alpha waves, which are linked to the flow state, and decreases beta waves, which are associated with higher levels of arousal and outside awareness. There’s even a company founded around this entire concept, called Focus@Will. Specific music tracks are selected and played over a period of 100 minutes to maximize this alpha/beta effect in the brain and enhance concentration. (You can check out the science and impressive amount of research that went into creating this service by visiting the site.)

As with so many aspects of modern living, part of training our brains to adapt to our new environments involves our ability to recognize the root of what we want to transform and working with what’s there rather than trying to constantly fight the outward symptoms of what your brain is doing. For example, someone might think that if she just gets into a space that’s completely quiet, she’ll be able to focus better — but that might not work for her if the quieter environment means that her brain just becomes even more hyper-attuned to any tiny distraction. Or someone might think that plugging in headphones and his favorite music will help his tune out the noise in a coffee shop — but if the music he’s listening to is too fast or has words that evoke memories or heightened emotion for him, then his locus coeruleus might be firing up without him even realizing it, causing a stress response that will inhibit his ability to focus! Each person is a little different, so some tools might be more effective for one person and not for another.

What about you? Are you ready to learn about more ways to tap into your higher brain for better focus and increased productivity? Come to one of our upcoming community events! They are fun, free, and filled with high vibrating like-minded people. Come solo or bring a friend. View all of the upcoming events and details now by clicking here.

Sources:

Aston-Jones, Gary, Ph.D.; Monica Gonzalez; and Scott Doran. “Role of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in arousal and circadian regulation of the sleep–wake cycle.” (pdf)

Conrad Stöppler, Melissa, MD. “What is the role of the locus coeruleus in stress?” September 4, 2013.

Gladwell, Malcolm. Blink: The power of thinking without thinking.